Tucked away in corners and niches, invisible in spite of being large and red, the fire extinguisher is one of the most controlled objects in our environment. Manufacturing standards for fire extinguishers in the USA are stipulated by the Underwriters Laboratories. The National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) regulates their use and maintenance with a national code; in addition to a fire code formulated by each state. Each extinguisher, therefore, bristles with the seals and certifications, the panels of instruction and information that painstakingly ensure its compliance with all these rules. However, outside the 15 seconds it takes for them to empty their contents (as stipulated by the NFPA), they hold little meaning or personal significance for their users.

This wasn’t always the case, especially in the days when the only way of fighting a fire was to hurl a bucket of water at it. A law passed in 1687 called for every citizen of New York to own one leather bucket for every chimney, clearly marked with the initials of the landlord. These were to be at the disposal of firefighters in the event of a fire, and failure to comply would result in a fine of six shillings. Yet, leather fire buckets from the 1700s were beautifully crafted objects, often carrying a painting of the building or a portrait of the owner. They were clearly objects that people were proud to possess, whether or not the City required it. In 1803, a group of citizens in New York actually took up arms against city officials because their buckets were not being returned to them after the fire had been extinguished. This event has gone down in Fire Department history as the Great Bucket Revolt in the Third Ward.

The Babcock fire extinguisher was the first popular fire extinguisher that resembles the ones we have today: a portable metal canister with a hose attachment that sprays pressurized water at a fire. Introduced in 1870, it was always positioned as a consumer product. In September 1871, for instance, the New York Times reported that a successful demonstration of the Babcock fire extinguisher had been held on the corner of Canal Street and East Broadway, “in the presence of a large and interested multitude.” The extinguishers were aggressively marketed with humorous advertisements that hinted at other possible uses for the extinguisher’s pressurized jet: replacing corporal punishment in schools, or calming down Mt. Vesuvius. Little or no mention is made in these advertisements of fire codes or city regulations.

The Babcock’s main competitor in the 1870s was an unobtrusive device called the Hand Grenade Fire Extinguisher. Decidedly cheaper, it consisted of a glass vial filled with an extinguishing liquid, usually Carbon Tetrachloride (CCl4). The modus operandi was idiot-proof: aim at fire and fling. Equally popular in warehouses and ballrooms, hand grenade extinguishers came in beautiful tints and shades of glass. The most popular brand was Haywards, but it was not uncommon for mantelpieces to be adorned by cut crystal hand grenades that looked more like expensive decanters than critical safety devices. The hand grenade continued to be used for a surprisingly long time. It is only in 1954 that the NFPA clearly states in its Fire Protection Handbook that hand grenade extinguishers were no longer acceptable to the Underwriters Laboratories. Studies had found that CCl4 decomposed at high temperatures to produce the toxic gas Phosgene.

The biggest breakthrough in portable fire extinguishers, however, was the development of the Soda Acid fire extinguisher. The technology had been available since the British inventor William Phillips patented what he called a “Fire Annihilator” in 1849. The idea was simple - the user pushed a knob which broke an inner vial of sulphuric acid into an outer container of Sodium Bicarbonate solution. This produced carbon dioxide and sodium salts mixed with water: a potent fire extinguishing combination that was released under pressure from the extinguisher. It was extremely effective, but apparently not very cost efficient: Phillips’ extinguisher had a number of tiny components that required careful manufacturing. As a result, it was aimed at larger establishments – industries, warehouses and hospitals – rather than private dwellings.

The credit for creating a safe, user-friendly Soda Acid fire extinguisher must go to an inventor and manufacturer from Boston, called Arthur Campbell Badger. In the period between 1904 and 1925, he filed a number of patents for Soda Acid fire extinguishers. The first of these established the generic form of the extinguisher. Users could now turn a wheel that screwed down to break the vial. This took considerably less effort than banging a knob, besides being immensely safer. Subsequent patents were for extinguishers that could be deployed in any position and fire extinguishers with anti-freeze. Clearly, Badger was an enterprising man in the best American tradition of the inventor.

Little is known about his life. A census record from 1900 identifies his birth date as 1861, and his profession as “Manufacturer, Copper.” This makes perfect sense, given the fact that early fire extinguishers were all made of copper, or copper alloys. It must have been around this time that he established the Badger Fire Extinguisher Company. The company itself has changed hands many times since, but survives today as Badger Fire Protection: one of the largest manufacturers and retailers of fire protection devices, with annual sales of over $22 Million.

All Badger’s modifications didn’t really change the target audience for the Soda Acid fire extinguisher. It was still aimed at larger establishments, while private individuals were sold simpler products by companies such as Pyrene. An advertisement in the 1936 Sears Roebuck catalog demonstrates this, but it also points to a new trend: fire extinguisher advertising had gradually become less about personal safety, and more about compliance with city regulations. In his pre-WWII term, Mayor La Guardia worked with Fire Commissioner John James McElligott to introduce a series of reforms in the fire department, including stricter enforcement of the fire code. In 1936, La Guardia prophesied on WNYC, “With modern fireproof structures, with our great increase in the number and quality of our fire engines, with our advent of training programs, the large fires will become almost a thing of the past, and I can foresee the day when the department is almost cut into half.”

Fire extinguishers continued to change considerably over the war years and the following decade. The City administration, in its effort to increase the efficiency of the Fire Department, took on a watchdog role by creating ever-more stringent fire codes. In 1954, the NFPA code and the NFPA Fire Protection handbook list lengthy rules not only about the use of fire extinguishers, but also about their positioning and maintenance. For example, a lead-and-wire tamper-proof seal was issued by authorized agencies, which indicated that a fire extinguisher was ready for use. Also, several new fire extinguishing chemicals and technologies had been developed over the war years. The code lists all of these, and provides illustrations of the extinguisher models approved by the Underwriters Laboratories.

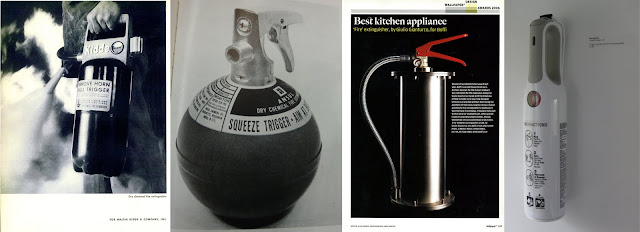

Fire Extinguishers were not ignored in the post-WWII golden age of American Industrial Design. The star designers of the era, Raymond Loewy and Henry Dreyfuss both designed fire extinguishers for rival companies. Raymond Loewy’s client was the chemical giant Ansul, and Loewy’s office designed two models for them in 1954 and 1955. Uncharacteristically, the Loewy designs are unadventurous and don’t differ very much from the models already available. Loewy lost the Ansul account to an up-and-coming design firm called Latham, Tyler and Jensen (LTJ). They designed a truly remarkable disposable extinguisher for Ansul in 1960, its globular form recalling old hand grenade fire extinguishers (which were also disposable). Henry Dreyfuss worked for Walter Kidde and Co., creating a novel extinguisher design with an extremely simplified lever and the beautiful terse instructions “Remove Horn/ Pull Trigger” rendered in Futura.

In spite of the fact that Walter Kidde and Co. now owns Badger Fire Protection, very few of the innovative design features from the 1950s have survived to date. The modern fire extinguisher would be easily recognizable to Arthur Badger, barring the illustrations and the coding system (which was changed in 1997). This is probably because the bulk of the market for fire extinguishers are public buildings and large establishments, while sprinklers and alarm systems have taken over fire protection duties in private dwellings. Nonetheless, there have been some recent attempts at redesigning the fire extinguisher. Giulio Gianturco’s stainless steel design for Boffi won the Wallpaper design award for 2006, but it seems nothing more than a cosmetic makeover, intended to fit this ungainly object with high-end kitchens. The Home Hero Fire Extinguisher by Arnell Group LLC, which won the 2007 IDEA award, seems a more honest reconsideration, with its radical handle/trigger design.

Notwithstanding these sporadic attempts, the fire extinguisher seems to have passed its heyday as a consumer product. Several factors have worked towards this. The massive improvements in fire retardant materials mean fewer fires, and fewer occasions to actually use an extinguisher. Also, the weighty regulations have essentially ossified fire extinguishers and firmly entrenched the few companies who produce them. It is doubtful if designers can now rescue it from its fate as a utilitarian engineered device; and revive its historical status as a designed, user-oriented product.

Pouring the contents of the teapot over the fire Holmes had started on the Persian rug.

ReplyDeleteWhat a great history and write up on the history of Fire Extinguishers. I especially enjoyed the images you have sourced. Although I have seen those sofas that 'self extinguish' a fallen match or cigarette for example, I still believe there will always be a need for some sort of fire extinguisher, although I wouldn't suggest the technology inside it would change too dramatically over the years.

ReplyDelete